on

Taking Advantage Of Being Medicated: Revising Pre-Medication Processes.

Recently, I’ve been forced to consider precisely how I do things, how I work and how I do what I want to, and what is expected of me. A lot of assumptions about how I work and how I can do well have been trained and engrained for decades at this point, and they essentially all became obsolete to varying degrees once medication was officially administered.

Yet, I haven’t really changed how I do things based on this obsoletion. A lot of things I still do now exactly as I did them before medication was available to me. The process still revolves around externalising everything, factorising and decomposing the projects into small slivers of discrete action to be done at a point separate than the planning. I’ve not taken into account how medication changes the asssumptions those ways were built on.

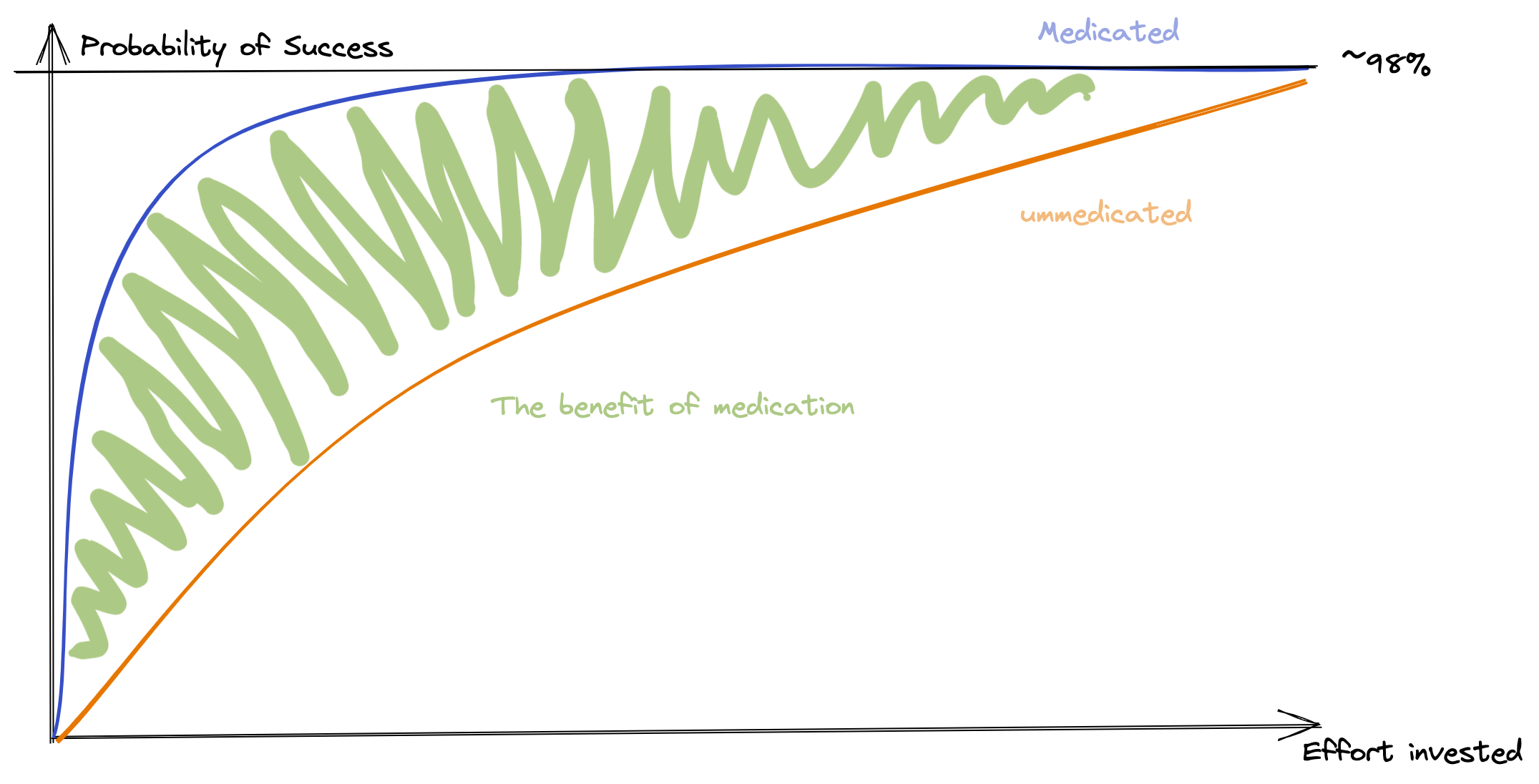

After some mulling about how I would precisely describe the impact of medication on my wellbeing, I arrived at a model: Medication lets me do better with less effort. In a graph, I’d roughly express the probability of a project succeeding against the amount of effort invested in the project like this:

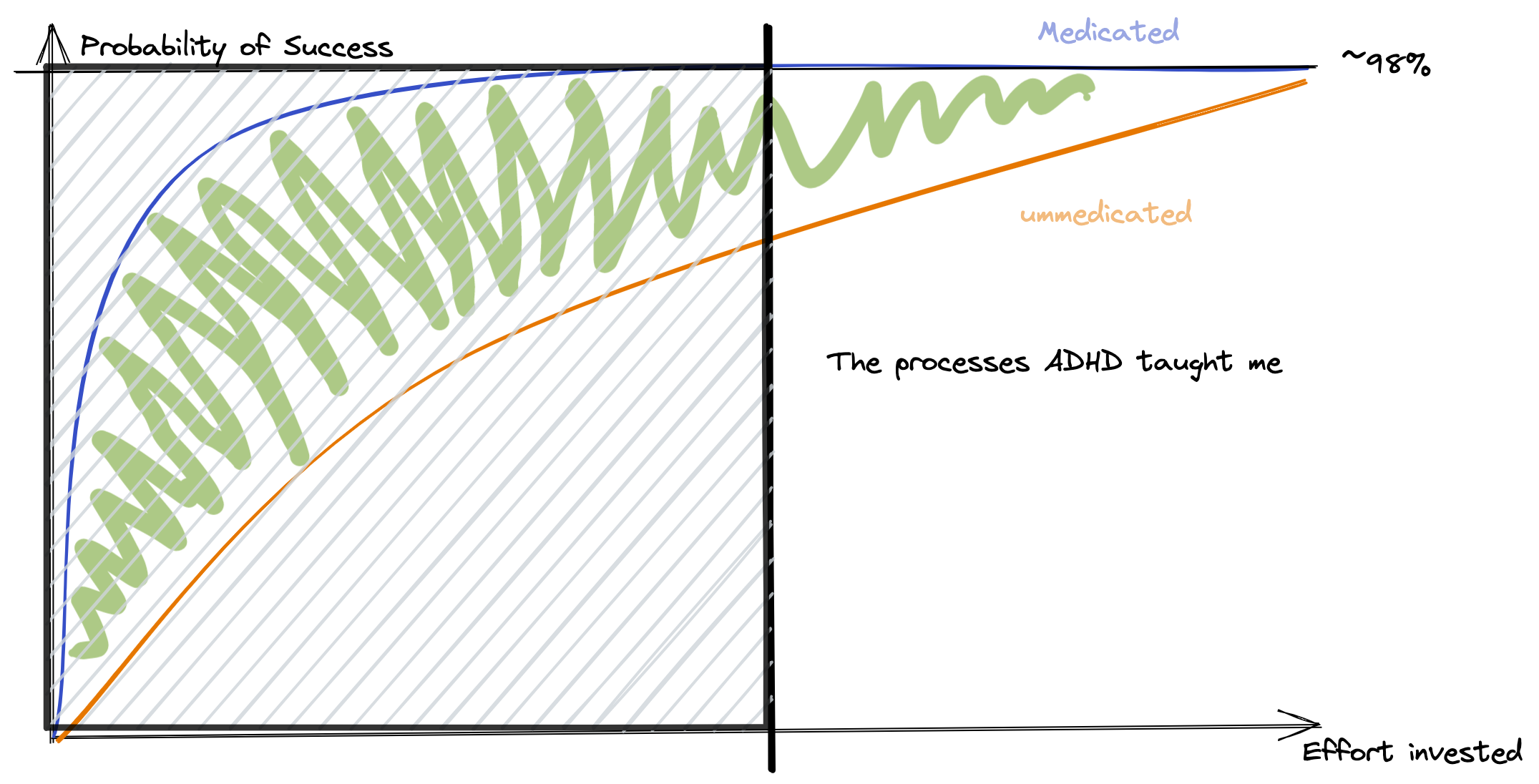

Now, the low probability of any project being completed successfully at low effort-levels is not practical or acceptable for daily life. The answer, at least for me, was found in using process, and tools to remove the low-probability-part by force. Everything got decomposed and split into tiny chunks, written down elsewhere and tracaked. This is to say, the processes made sure that a certain level of effort is invested in everything that needed to be done by me, so that the bottom for successrate is at least acceptable:

Not only is this a very tiring way to go through life, it also removes a large part of the benefits of medication, while leaving all of their problems intact. The processes, strategies, habits have to be re-thought and re-engineered, from ground up, as the assumptions and context for which they were designed no longer holds water. A lot of energy is wasted by overprocessing.

This is, to put it mildly, daunting. These are the processes that have kept me alive for decades, allowing me to function and to thrive as much as I did. I have more than a few engrained pieces of muscle memory regarding workflow, kneejerk and trained automations on a cognitive level. But all of them together significantly reduce the benefit that I get from being medicated, and the opportunity cost is significant.

The differences in behaviours, the things that have in fact changed, lay the groundwork for where I should go first for changes to existing processes:

- It is no longer straight-up impossible to go from “deciding on doing something” to “doing it” immediately. Previously, before medication, this required a pause, as “deciding on what to do” was considered a step, and this created a barrier to the next action.

- I have a larger “working memory”, I can remember contexts and facts that aren’t immediately in-context. This means I have to externalise less, and can rely on having a reasonable memory. What this means, and where the boundaries are of this, I will have to explore.

- Sustained focus is now possible, meaning I no longer have to decompose everything to minute-long slices, and I can use larger chunks as process input. This makes planning considerably less tiring, and planning a day easier. The mental barrier of “oh that looks too large to do” remains, and will have to be carefully eroded.

- Sustained focus also means that activities I previously had aversions to are now possible, and I need to re-examine that entire list. People who have followed me for some time on Twitter will note that my reading sharply increased (from zero to not-zero) when I gained access to medication.

- Spontaneity is now no-longer day-ruining. I combatted lack of executive function with careful planning and precise habits, this resulted in brittle, but functioning processes. I now can spontaneously do things without planning them before to grueling detail, something that previously would throw off my entire day.

On the other hand, it does not mean that all habits and processes are now actually obsolete. I still get incredible mileage out of my project planning/task management systems, but now they are “merely” beneficial instead of absolutely necessary.

It boils down to the same decision as always: Adapt to the new context, or risk eating larger and larger opportunity cost. So, in this vein, adaptation. Time to see how the new, changed, mental landscape looks.